A sophisticated and increasingly aggressive al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) has propelled the Republic of Yemen to the top of the Obama administration’s war on terror priority list. Yet amid this news-catching and billion-dollar geopolitical struggle against religious extremism, Yemen is experiencing another important religious phenomenon.

Zaydism is a branch of Shi’i Islam distinct from its counterparts in Lebanon, Iraq, Iran or elsewhere. The story of Yemen’s Zaydi community begins in the late 9th century, when the Zaydi scholar Al-Hadi was invited by tribes in Yemen’s northern highlands to resolve their intractable disputes. Accepting Al-Hadi’s governance, these tribesmen ultimately were absorbed into a Zaydi universe, embracing Zaydi political authority, theology and law, in addition to their local tribal customs. In this part of Yemen, temporal power and religious doctrine were united in a uniquely Zaydi form of theocratic rule known as the Imamate. Though never permanent and rarely stable, at its pinnacle the Imamate’s influence extended from present-day Saudi Arabia in the northwest, to the Gulf of Aden in the south, to western Oman in the east. Particularly in Yemen’s northern highlands, history was defined by the activities of Zaydi rulers, judges, scholars and tribesmen.

For over a millennium, the Zaydis of Yemen enjoyed an unparalleled history of political rule, intellectual production and pious devotion.

This all changed dramatically with the Sept. 26, 1962 Republican Revolution. This decisive moment in Yemen’s modern history unleashed an eight-year civil war in North Yemen—South Yemen remaining under British control until 1967—between “nationalists” supported by Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Egypt who sought a new direction for the country, and “royalists” who continued to back the ruling Imam, supported by Saudi Arabia. Ultimately, it led to the Zaydi Imamate being replaced with a distinctly Republican and nationalist government, complete with modern bureaucratic institutions and a pronounced antagonism toward the former ruling Zaydi tradition.

The Revolution inaugurated a volatile era for Zaydi adherents in Yemen, and today this community sits on the fringes of Yemen’s public arenas of culture, religion and politics. For a tradition that once dominated large parts of Yemen, its present-day irrelevance is remarkable.

This marginalization has coincided and been reinforced by the “Sunnification” of Yemen. Over the last 40 years, the country has seen the growth of a loose but powerful alliance of political parties and ideological groups that share a commitment to Republican nationalism and Sunni-based reform. With roots in the Imamate period, this movement has promoted anti-Shi’i attitudes and built a potent wave of opposition to Zaydi thought and adherence throughout Yemen. Unlike al-Qaeda, these groups operate within the mainstream of the country’s religious, social and political spheres.

The most dramatic consequence of this phenomenon is the turning of large numbers of individuals and communities in historically Zaydi regions toward Sunni Islam. These range from what might be called “Zaydis in name only”—nominal Zaydis with minimal commitment to Zaydi Islam’s tenets and history (President Ali Abdullah Saleh being one example)—to aggressive opponents of Zaydi thought and practice. Significantly, this retreat from Zaydism has been part and parcel of the official state-building effort in Yemen, as the new Republican government sought to weaken the former ruling group and foster a national religious identity that transcended traditional boundaries and identifications. In doing so, it has consistently promoted alternative religious and political visions, while pushing the Zaydi tradition to the periphery of Yemeni society.

Whether in schools, media or the political sphere, this process continues today.

In fact, the very future of Zaydi Islam in Yemen is in question. The urgency is not lost on the Zaydis themselves, and in response their leaders are advocating for their community and religious tradition in several important ways.

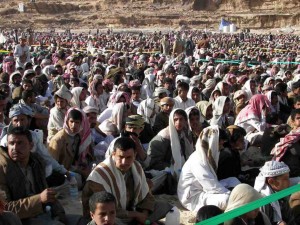

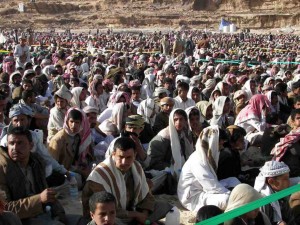

The “Huthi conflict” is the most prominent example (see “Is Yemen Breaking Apart?” by Patrick Seale, November 2009 Washington Report, p. 31). The Huthis are a group of Zaydi sayyids (descendants of the Prophet Muhammad), supported by a wide range of tribal allies, who have been embroiled in escalating violence with the Yemeni government since 2004. The sixth round is now in the midst of a highly tenuous cease-fire. Although this crisis was sparked in the province of Sa’dah, historical capital of the Zaydi Imamate, the Huthis and their supporters have now formed a quasi-government in several of Yemen’s northern provinces. The conflict has severely drained the country’s national economy and produced large numbers of internally displaced people, although it only captured mainstream media attention last winter, when violence spilled into neighboring Saudi Arabia.

A Complex Crisis

Often mischaracterized as a religious struggle between a pro-Sunni regime and Shi’i separatists, this complex crisis cannot be pigeonholed into one of pure sectarian interests. It was stoked—and is maintained—by several interrelated factors, including longstanding historical grievances, tribal loyalties, access to government services and the political legitimacy of the Saleh regime. Furthermore, the Huthis’ stated goals continue to evolve and have ranged from the right to express religious slogans, to application of the Yemeni constitution, to basic self-defense.

Viewing the relationship between Zaydis and the Yemeni state through the lens of the Huthi conflict would be a mistake, as the Huthis represent a political-religious movement that emerged in the specific context of Sa’dah and its vicinity. Still, the situation does allude to a much broader struggle since 1962: one over Zaydis’ communal identity and rights in the Republic of Yemen. In many ways, this crisis is characteristic of the challenges confronting the Zaydi community in Yemen today. On the one hand, it has led to intensified repression and further marginalization in both official and popular spheres. Yet it also reflects a broader pattern of renewed advocacy for Zaydi thought, history and identity.

Zaydi adherents point to a “Zaydi revival” since Yemen’s Unification in 1990, emerging in the context of a nationwide loosening of restrictions on diverse ideologies, whether Zaydi, socialist or otherwise.

The lion’s share of this advocacy reflects a political quietism. These efforts focus on educational outreach and publishing Zaydi texts, especially as dwindling knowledge of Zaydi Islam has coincided with the rapid spread of anti-Zaydi thought. For example, at the Imam Zayd bin Ali Cultural Foundation in the Yemeni capital of Sana’a, thousands of Zaydi manuscripts have been digitized and catalogued in an effort to make these seminal texts accessible to the Yemeni public and beyond.

Key Zaydi scholars are also reinterpreting core Zaydi doctrines to reflect contemporary realities and sensibilities, and, ultimately, to make their tradition more relevant in Yemen today. One example is the classical Zaydi concept of khuruj, which refers to the imam’s “rising up” in rebellion against an unjust government—a doctrine frequently cited to demonstrate the Zaydi threat. A number of Zaydi scholars now speak of a “constitutional khuruj.” Stressing Zaydism’s unequivocal commitment to political justice, they have transformed the means for undertaking khuruj from physical seizure of power to nonviolent and democratic change.

Regardless, entering the realm of Yemeni politics is precarious, especially for Zaydis labeled as “strict,” or those with a more pronounced ideological commitment to their tradition. Politically active Zaydis are forced to walk a treacherous tightrope of criticizing the Saleh regime’s behavior on the one hand and expressing allegiance to the Yemeni state on the other. While that may hardly seem revolutionary (particularly considering the high levels of nationwide opposition), for the Zaydi community accusations of disloyalty or sectarian fanaticism are inevitable.

Many Zaydis blame the regime for exploiting an unfair choice: demonstrate your allegiance to the Republic and support this particular regime, including its controversial actions in Sa’dah; or, alternatively, criticize it, meaning your loyalty lies with your community alone or even outside the state. The Huthi conflict has only heightened the government’s paranoia of Zaydi activism.

Zaydi advocates are breaking down that choice. As loyal Yemenis and committed Zaydis, they assert their individual rights as Yemeni citizens and their collective rights as members of the Zaydi community. Not only do they seek to remind Yemenis of Zaydism’s decisive role in the country’s history, ancient and modern, they also insist that the contemporary Republic is more than simply an anti-Imamate or anti-Zaydi state. Instead, they are adamant that it must embody the Islamic (including Zaydi) and Republican principles of justice, democracy and development. While they may object to the 1962 Revolution’s ultimate course, epitomized in Zaydism’s present-day marginalization, they defend the transformations it wrought as a progression toward ideals they embrace but that remain unrealized.

In doing so, these activists represent the repression of Zaydism as a national issue—rather than a communal one—that reflects the ongoing struggle of all Yemenis to build a country defined by equality, freedom of belief, security and prosperity. Although the Zaydi community’s disenfranchisement has a distinct ideological tenor, this story of conflict, underdevelopment and political manipulation is indeed a national one in Yemen today. Essentially, these Zaydis have placed their community and their country on a parallel trajectory toward democracy and justice. Some even depict the divisive Huthi insurgency, which has cost the Zaydi community dearly in terms of public image and reputation, as an essential part of this larger Yemeni struggle.

These Zaydi leaders are advocating for what they believe are Zaydism’s singular solutions to Yemen’s political and social crises. (As one example, they contend that its spread will provide a significant elixir to Yemen’s religious extremism problem.) If successful, they will take the question “is Zaydism disappearing in Yemen today?” and redefine it as “are the ideals of the Revolution disappearing in Yemen today?” Whether through political and human rights advocacy or educational outreach, they are working to ensure that the answer to both questions is “No.”

By James R. King is an independent analyst, specializing in Zaydism, Yemen and the broader Middle East.